I asked my mother if she ever thought she’d find herself sitting naked on a toilet in Africa with a shaved head and a tattoo on her hip.

She thought about it. No, she hadn’t, she said.

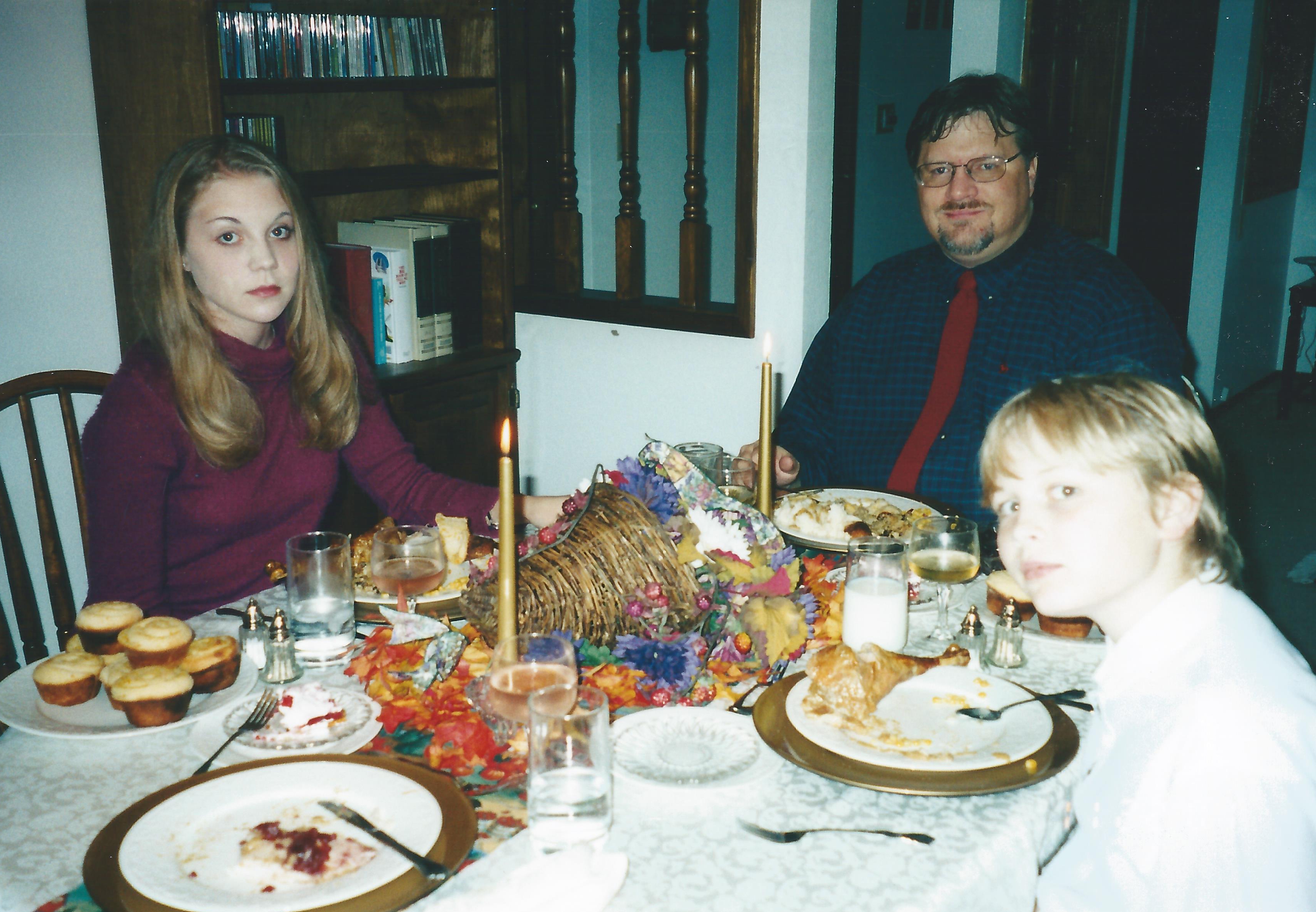

She and Dad have come to visit us and their grandson for three months. Her head was not yet shorn when she arrived.

In the mornings, she and I walk into town to have breakfast on the porch of the Ta Da! Cafe. Afterward, we shuffle down to the beach. Her hip has been bothering her. She smiles at everyone on the street and says good morning brightly. Even to the man picking through the trash, who begins walking behind us as we approach the secluded dunes.

He makes me nervous and I’m short with her when I say, “This way, Mom!” as she slows to admire a plant. The man was harmless, of course.

Sometimes, her brightness irritates me. When I’m around her I feel the rise of primal emotions, ones which only she can trigger and which I seem to be able to do nothing about. One of them is that I’m occasionally, helplessly, embarrassed by her.

It’s not fair to her. But the likeness between my mother and me feels too private for other people to see.

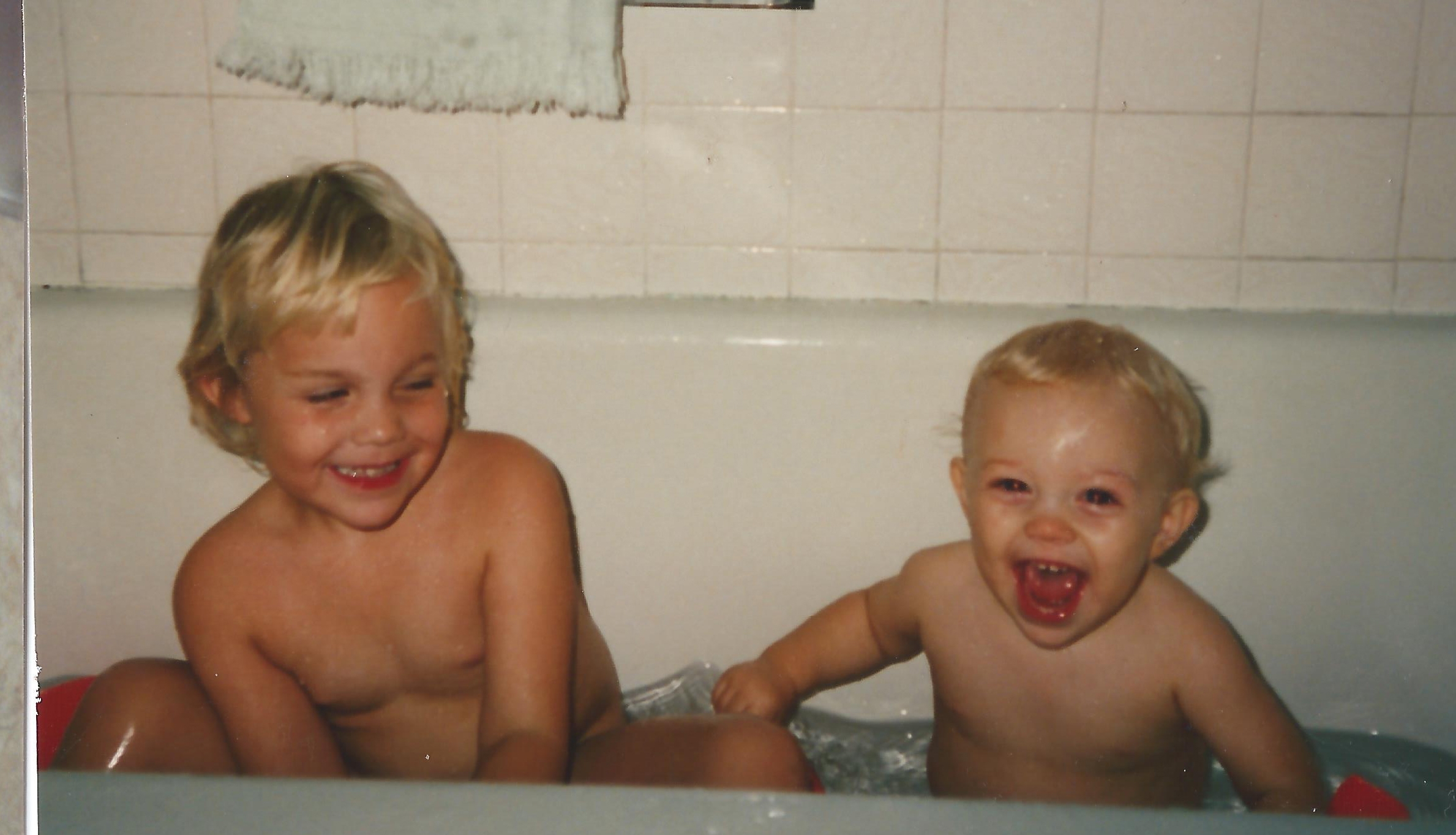

Growing up, we had vicious fights. My brother and I bickered constantly, stoking the helpless rage that always smoldered in her back then. She told me later that she felt like she was boiling over. Her lips would tighten and her nostrils would flair. Spencer and hid if we could, but if we were stuck out in the open we were as helpless as wildebeests waiting for the leopard.

We would get it. I reflexively covered my butt with my hands whenever I was walking in front of her.

She took us with her to the grocery store and the bank, toting us around with her coupons clipped, slogging us back home through the snow. Once my brother lost his boot in the middle of the slushy boulevard and he was so angry hopping on one foot that Mom and I couldn’t stop laughing. That was a happy moment.

Her brightness now is an answer to her shame of the rage that overcame her when I was little, rage that would send her fist knocking into the back of my head.

Her rage was her own. But I wonder now if rage besets every mother who feels, at some times, alone. Sometimes when I have Spencer’s pacifier in my mouth, because my mouth and feet have become extra hands when two are not enough, I feel the urge to bite it so hard that it’s destroyed.

My son isn’t even old enough to be cruel, and children are so cruel. If I ever wanted to get back at my mother, all I needed to do was to kick my little brother until he cried.

Of course, there were starlit sled rides. When she wasn’t in the thrall of her rage, she made everything magic. When the snow was falling so fast and deep that she couldn’t drive The Little Brown Turd, she would pick us up from daycare with the sled. It was an old-fashioned wooden sled just big enough for my brother and I to squeeze close, hugging my mother’s school bag, and she would pull us home through the empty streets. The moon was bright on those nights, and when we laughed, it echoed loudly.

She was crafty. While I’m adventurous like she is, I inherited nothing of her skill for handiwork. She once built an outdoor enclosure for our cats out of chicken wire. She wired a TV in the kitchen to be a satellite of our TV in the living room so that we could all watch a movie at the same time from different rooms. This was in the 90s. Now, she tells me about new apps to try, and sometimes around her I feel old-fashioned.

She had wavy brown hair then, and it flew behind her when we rode our bikes in the summer. Spencer would sit in a seat attached to the back of her bike, and I rode behind her, on our adventures.

In high school, I was too old for that. My mother and I fought again. Sometimes I would make her cry. I was used to anger. I didn’t think crying was fair.

Her rage came in shorter fits, which she managed to control most of the time. We began to talk about everything. In the Arby’s parking lot, she told me about the drugs she had done in college. We became close. If I had ever gotten pregnant before I was meant to, I would have told her.

She is different now. Her hair is coarse and mostly gray. She is clumsy, but only around me, she says. She spills soup on the front of her shirt, and trips on the lips of rugs. I feel a pang in my stomach to know that something about me makes her nervous.

But also, she is still the same. She adventures. She will try any food at least once. She will try anything, actually. Visit me anywhere in the world.

She gets tired more easily now. She will play with Spencer for hours on the floor, but she goes to bed early and sleeps in, which she never used to do.

When she goes to bed she reads, studying books about Hout Bay where we live. She takes immense pleasure in learning about the places she visits.

Did you know, she said, that when Simon Dorman and his family moved here, they never heard from their family in Lithuania again after WWII. They’d all been wiped out. It just hit me, she said.

In the middle of the night, if I can’t get Spencer to fall back asleep, sometimes I just give up and lie there holding him while he cries. My mother comes in then, and holds out her arms.

It was soon after arriving here that she got sick. It was a terrible flu that creased her face in pain and made her unusually quiet. I’m frustrated when my mother doesn’t feel well. I’m amazed at the childish emotions that rise in me, perfectly preserved after 20 years. I have to stifle my frustration with her at being sick, as if it were her fault.

There is no rage in her now.

When the heat of this place became too much for her, she decided she wanted a haircut. I knew on the first day that the heat was too much for her. I wonder if everyone can read their parents’ faces so easily.

When she asked if I wanted to cut her hair, I was all for the idea at first. I pictured myself biting my lip in concentration, artfully making a snip here, a snip there. Then she began to tell me how to tell if the layers are even, and I’ve never taken lessons from her very well. It was going to be more work than I’d thought. I couldn’t just make an art project out of my mother’s head.

Unfortunately, I had already made a mess of it.

She wasn’t angry. Shave it all off then, she said. I’m in South Africa, I can do what I want.

I shave it all off, letting big gray clumps fall onto the tile. When it’s finished, I am afraid to touch the prickly gray stubble, and her scalp underneath it. I’m afraid that the skin there will be too soft, too delicate.

In her exuberance for life, my mother would rather die early than grow old, and that frustrates me too. Sometimes I feel selfish around her. Sometimes I feel cold.

While she’s recovering from the flu she spends a lot of time on the toilet, and I walk in one night to find her naked, playing solitaire on her phone. The overhead light shines on her skull, and I can see the bright tattoo on her hip.

There are actually two tattoos, which she had done after my brother and I went away to college. She designed them herself. One is a blue and green embrace of two fish, the other is a music note winding around a red and orange sunburst. The music note was for my brother, the fish were for me.

She used to take me to the hospital in the middle of the night when I was sick. I hardly ever get sick now, but as child I was sick all the time. I came to love the smell of a hospital, and the way the lights from the ceiling made overlapping pools of light on the floor. While we were waiting for the doctor, she would rock me to sleep.

One day she and I are walking to the beach and I see a steep curb ahead that I’m not sure if she’s seen. I grab her elbow and say, “Watch out, Mom.” She looks at me, startled.

We both know that things are changing. I wonder if I will ever rock her to sleep in the warm dark of a hospital room. I wonder what it will feel like if she loses her memory as the women in my family often do, and looks up at me in confusion. I wonder will I be able to bear that, holding her like a daughter.

She will have made all of her amends already. Her rage was buried long ago. She is always transforming herself, and the only sadness in that hospital room will be mine. She is that kind of a woman.

Leave a Reply