(a continuation of the Giving up the Script series)

We’d sold our house. Now we had to sell everything in it to become digital nomads. We’d been living together since 2009 and had never done a serious purge. Though we’d moved several times, Amazon always paid to pack everything up and unpack it again. We put such little effort into moving to Luxembourg in 2012 that we found ourselves unpacking 120v light fixtures, blenders, and toasters when we got there. Seriously Past Me, how much effort does it take to give away a toaster?

In addition to never throwing anything away, we accumulated more stuff every year. As we made more money, our apartments got bigger, and as our apartments got bigger, so did the obfuscation of the metastatic nature of consumption. We didn’t mean to be excessive. We just wanted two bedrooms so relatives could visit and we were lucky to find a three bedroom in Luxembourg for a fantastic price, which is always a good justification for spending.

The apartment came with two extra all-purpose rooms. Now. You have to fill those rooms. Don’t you?

Although we spent the most on food, drink, and travel, we also bought plenty of things we didn’t need. We bought a full set of Le Creuset pots and bakeware and some original art I’ve since decided I don’t like. It’s currently on display at a little gallery called Mom’s Basement. During a 2013 trip to Sweden, I bought a funky little woman made out of wood, oyster shells, and moss, for $500. I named her Begonia.

I’m not alone. My last boss’ 25-year-old brother was a Google developer. He lived in an apartment that was empty except for a huge, ridiculously expensive world map as a backdrop for his gaming weekends. She mentioned it when I asked about her weekend plans and she said she was going to go buy him some kitchen utensils because he didn’t really own anything other than the map. How did we get to $6,000 maps and no utensils? What other stupid things had I accumulated, and why?

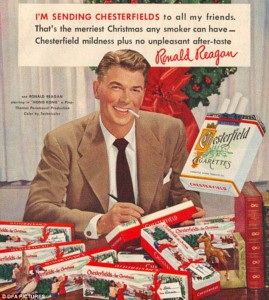

The baby boomers bought their houses and filled them slowly with treasure. Slowly is the key word, because making it to the middle class took hard work. I grew up in a kitchen full of appliances but my grandparents had to earn their washer dryer combos and teflon coated ovens. As the 60s and 70s progressed, slowly turned into quickly as banks learned how to enable their own addictions and ours by offering us lines of credit and adjusted rate mortgages. As our purchasing power increased, so did the ways we wanted to use it because at the same time, alchemist marketers were transmuting commodities into the secret of eternal happiness. We found more things we decided we wanted. Ironically, the more we bought the less meaning each purchase held for us, and we began buying things continuously, out of habit. If you’ve seen Mad Men you know that emotional branding was in full swing by the 1960s.

In other words, we made a science of trapping our dreams into things that could be touched and held. Noble strivings toward a happy household, toward adventure, toward kindness, toward innovation, were conflated with brands out for profit, which aren’t necessarily bad things in themselves. The bait-and-switch is that eventually, the brand tugging on your heartstrings will have interests that diverge from your own, and it will be hard to untangle your attachment.

So with the help of the financial industry and the malleable nature of capitalism, we equated the good life with a house full of stuff, confused things for feelings. By the time I was a 2 yr program manager and making as much money annually as my father made after a long career culminating in his role as Vice President at his small company, my cohort of young corporate tech employees had long been programmed to seek well-being through attainment. Even the Google developer. He valued knowledge and exploration but his first instinct toward achieving it was to buy a map. The map was his washer dryer combo, but it doesn’t mean much when you achieve it at the ripe old age of 23.

The developer would be about 30 now, and I was curious about what became of him. After some internet stalking I found out that he eventually gave up the map for actual travel. His Facebook wall shows pictures of himself at a wolf reserve throughout several trips to Tanzania. How did he, a workaholic tech employee, make the time to replace symbolic purchases with actual experiences? He didn’t. He quit Google to work at a start-up.

In our twenties we were all about learning, climbing, discovering, pushing our alcohol tolerances. We weren’t thinking seriously about the possibility that the money might not always flow so easily, that we might at some point be insane enough to quit our jobs, if they weren’t already outsourced. We bought outrageously priced oyster shells and named them. Or maybe only I did that, but you get the picture.

Bernie Sanders knew in 2003 when he ripped Alan Greenspan a new one, that it’s not just manufacturing jobs we’re losing to automation and outsourcing. White collar information technology jobs are increasingly vulnerable as high education attainment rises globally along with the technology that makes remote work possible. So even if you love the script you should have a Plan B because it doesn’t love you. It doesn’t have feelings. It’s not a person. It taught you that achievement was a feeling you could buy and if you ever find yourself unable to continue buying those feelings, you’ll go through massive withdrawal. We did.

What we learned as we started to sell everything to become digital nomads was not that we were on the path to becoming monks, or even dirty hippies. After all, we live in a capitalist society in which spending is a hard requirement for the economic world to keep turning.

We simply began to think of our purchases much more clearly, in terms of whether they were serving emotional needs best served by actual work and activity, whether they were long term investments (and the attendant rules for deciding what constitutes an investment), and whether they were valuable trade-offs for our freedom.

We started to think of every new purchase in an entirely different way. Read about what we learned from selling everything to become digital nomads, both practical and spiritual, in our next installment of Selling Everything.

Leave a Reply